Blank pages

Keynote Address for the 45th Annual Congresso of the Luso-American Education Foundation, hosted by the Portuguese Beyond Borders Institute of California State University at Fresno

Warm greetings to all of you from New York City.

It is a distinct honor to give the Keynote Address to launch the 45th Annual Congresso of the Luso-American Education Foundation, hosted by the Portuguese Beyond Borders Institute of California State University at Fresno. Special thanks to Luso-American Education Foundation President Bernice Pelicas and Chairperson of the Board Joseph Resendes, along with University President for Fresno State Dr. Saul Jimenez Sandoval, and also Dean of the College of Arts and Humanities Dr. Honora Chapman, the Consul General of Portugal in San Francisco Pedro Pinto, and Vice President of the Government of the Azores, Dr. Artur Lima.

I am particularly grateful to Diniz Borges of the Institute for asking me to speak with you. He is one of the most tireless creative supporters of our community, and I treasure our long friendship. This honor was last bestowed upon me over twenty years ago in Berkeley, and I have an abundance of saudade for that because my father, August Mark Vaz, was present. He had given many such addresses himself as a distinguished historian and author about the Luso experience who wrote The Portuguese in California, still considered a landmark book.

Our speeches were, of course, live. It’s important to note the peculiar circumstances gathering us together today, thanks to the blessings of Zoom and computer screens – though with all attendant anxieties – at a time of global pandemic, something that drove every single one of us into a strange solitude with the irony of finding the whole planet there.

It’s appropriate to ask: Who are we supposed to be in this upheaval, this convulsion? What is education? What is the role of our cultural past and present as we look at a dizzying future?

Let me tell you a story that seems fitting. Long ago, two of my cousins in the Azores moved to the Bay Area and wrote continually, and with increasing exasperation, to convince their widowed mother to allow their remaining brother, the youngest, the one she adored, to join them. She was welcome too but refused to leave her garden and the graveyard bones of her husband. She finally relented and let her third son leave. But mere weeks after he arrived in California, he died. Because this was during the Flu Epidemic of 1918.

The horror story quickly slid into: How do we tell our mother? How do we answer her note demanding to know why her beloved boy has not responded about how he’s doing and if he got the Bolos Dona Amélia she sent?

Here’s what they did at first: They invented a life for him. They wrote to her about all the adventures he was having, the walks on the wharf of San Francisco, the fresh boiled crab, the excitement of being American, the new teaching job.

Eventually they wrote the truth, because their mother deserved honesty. But as a writer, I was dazzled by how they elected to fill a blank space, because unexpected tragedy forced them to get out and discover life, so they would have things to tell her. That is what authors look for, that place where imagination and invention are forced into a blank space, because it’s where stories reside. When I wrote “Heat Cannot Be Removed From Fire” based on these true events, I allowed the death of a brother to give the survivors an impetus toward fashioning their own destinies, if only to fill their own grieving hearts.

My point today—I suppose the one “takeaway” I’ll offer—is that so much of our world seems unpredictable that we’re facing a call to embrace rather than fear the unknown, to seek what we don’t know rather than adamantly insisting on answers. We live in a time of being asked to like or dislike everything, to rate it, a time of stubborn certainty, whether we’re experts or not. We award five stars, or none. We offer comments. It’s all very loud. But true education, I want to suggest, is always about finding the further questions, letting go of being right in favor of the uncomfortable push past conclusions into whatever lies in that empty or blank space beyond every answer you find. Maybe it’s time to add an “I don’t know” option.

I hasten to add that this attitude can inform all pursuits—in the humanities, sciences, or business—as much as it does writing. Success but also wisdom seem to involve a willingness to find peace and even an elegance in the discomfort of always seeking the next higher plane of not-knowing. Finally, it’s the best place to be as humans, not to be right but to keep ascending quietly toward a further mystery. I want to address what that means for the culture of our community, but first I’ll give you a helpful image from another story that a friend introduced me to decades ago by saying, “Katherine, it’ll tell you everything you need to know about being a writer, but also about how to live.” I didn’t believe this until I read Isak Dinesen’s marvelous story called “The Blank Page”—and sure enough, my friend was right.

The narrator of this ethereal, lyrical tale—it is fiction—describes a centuries-old tradition of the Portuguese royal family: When the daughters are married, they must cut out the section of their bed linens with the blood stains that prove their virginity. These are framed and hung in a hall of the castle, and visitors see roses, animals, and whatever they please in these blotches. But the framed linen before which everyone stands in the most awe, the one that reverberates in the recesses of all hearts, where the profoundest truths lodge, is completely pristine. Here, the blankness and silence suggest more passion, more betrayal, more rebellion, more possibilities, more anguish. Did the bride have another secret love, forbidden to her now? Or did she reject her husband? Why? There is no way of knowing for sure. But whatever is true is strikingly dramatic. This is the best description I’ve found for what creativity does: It disrupts our certainty by suggesting that many possible answers might lurk. Note that looking at that framed blank was not passive; a viewer actively engages his or her wildest imagination. Again: This was a made-up story, but it’s about a sizable truth.

As a child, I knew an Azorean immigrant named Mrs. Correira, a housekeeper to my godmother Clementina. Mrs. Correira could not read or write Portuguese or English, and she could not dial a phone because she reported that numbers looked like fishhooks on a beach. My father, out of nowhere, remarked, “I think she thinks in color,” and he prepared a placard with seven dots of tints alongside pictures of the police, the dairy, the hospital, our family, which corresponded to the blots of color he painted over the numerals on her phone dial. She could now telephone in color…this is the moment I became a writer, because to me the greatest metaphor ever was that we should find our own original, vivid language. But I’m ashamed to say that I was a sulky teenager annoyed at being sent over with the key! Mrs. Correia was afraid to knock on her neighbor’s door, and this neighbor had phoned my dad to report that Mrs. Correia had been sitting in her yard quite a while. I was impatient, and yet I was being handed out of the blue—there’s a color-word—a gift and purpose that has lasted my lifetime. This seems so pertinent a cautionary tale to me now, that we do best when we wait upon and absorb what the world gives us, rather than us always telling the world what we think. It’s a paradox that the older I get, the less I’m sure I know.

Any willingness to travel down plenty of mistaken pathways is humbling. I can vouch for this based on my recent novel, my sixth book, taking over fifteen years with countless missteps. But it began by recognizing I was being handed a blank spot where a treasure was residing. I was invited to give a talk decades ago at the Library of Congress in the Hispanic Division, and I viewed an exhibit in the Map Division about “The Portuguese Protestants of Illinois,” which made me laugh, first, and then piqued my fascination. In brief, a number of people in Madeira who had converted to Presbyterianism were violently driven off the island and later adopted by Springfield and Jacksonville, Illinois, in the time of Lincoln. Someone named John Alves was raised in jail with his mother, who was condemned to die for heresy, but what caught my attention in a newspaper interview with him late in his life is that he made a pilgrimage from the west as an old man back to the Lincoln household. A playwright was also a visitor in the house, conversing with the owner. John had fallen in love with and courted a young Madeiran woman named Mary he’d met there. (The Madeirans did odd jobs for the Lincolns.) The playwright said something that caused John to speak up and correct him about the operation of the fireplaces back in Lincoln’s era. The playwright insisted John give him a tour, and he took his arm and asked questions. When the farewell came and they were about to sign the Lincoln Ledger, John reported that his hand was shaking so awfully to recall Mary that the playwright had to inscribe John’s name for him. (At the Lincoln Library, the people in charge were thrilled when I asked them to get this Ledger from the vault for me. We marveled that John had recalled the wording verbatim during this heightened emotional moment.)

Here’s where the blank in his story occurred, the one I found in the newspaper article about John: After he joined the Union Army, apparently Mary and he, for unspecified reasons, lost track of one another, and he spent the rest of his life wandering. In his account, an entire year goes missing when he returned to Illinois after being wounded at Shiloh and traumatized in Vicksburg: She is not mentioned. So I thought: That is where the novel is. What happened?

I like to think he responded, because one day I was ready to give up. I walked home from my office at the Radcliffe Institute…and waiting for me in my apartment building’s foyer was a large packet about him from the Veterans Administration, one that I’d ordered but had magically arrived much earlier than it should have. It contained his army papers and a document about his terminal illness in a hospital, when he typed out, “I have no one to take care of me.” I told him I would try my best to do that. Lots of uncanny things like this happened. One quick corollary to my main point today about finding questions more than answers, to pressing the “I don’t know” button, to finding the blank space, is to tell students listening in that Google is a miracle, and it’s a boon, but the real discoveries happen when you go into the world and let it speak and surprise you. For instance, I was in Illinois doing research, and suddenly I was surrounded with this grotesque raining down of cicadas so thick they were everywhere, getting crunched by feet. A biology professor I’d met there said it was time for their thirteen-year hatching. Of course I put that in my novel! No way would I have found that on Google—and if I had, the feel of it and sound and look would have eluded me. I wandered into an old bookstore and found a pamphlet entitled “1849 Businessmen of Illinois”—and what a jackpot of names and funny asides about citizens, including “Mr. A. Lincoln, attorney.” James Joyce said that when we’re in tune with creativity, the world itself will blow a piece of paper toward our feet with the word we’re searching for. It’s fitting that as we grow older and head toward the real unknown, we realize the point of living with grace is to stand humbled by mystery, versus wanting everyone to admire how much we know. My book is in its finishing stages, and let’s just say there are limits to how many fifteen-year projects I have left. But a full life by definition will leave a lot of things unfinished.

I want to track back to suggesting some questions—not answers—about who we are as Luso- and Lusa-Americans: culture and the future. I’m not alone in taking pride in our immigration stories, in our ceremonies, in our worldview that magic can speak as an ordinary occurrence. We honor the past, we preserve our ghosts. But what’s ahead? How can we listen to blank spaces to find future answers involving baffling issues of identity?

Gish Jen wrote a novel called Mona in the Promised Land, about a Chinese-American young woman married to a Jewish man of Polish descent. It posed this very question, done with great humor but serious purpose: What does culture and ancestry mean to Mona, if she and her immigrant mother’s delving into being Chinese is limited to arguing if chopsticks can go in the dishwasher, now that they’ve “made it” in the Promised Land? Mona is haunted by phantoms of ancestors growing increasingly faint. How do we preserve memories in a community, blending varied sensibilities into a unity? What happens when the mythologies of our predecessors are allowed to speak more to us than our present-day anecdotes? How do we interact? What legacies do we create for our children?

Good time to press the “I don’t know” button, but I’ll offer this: I teach the Writing the Luso Experience every summer at the Disquiet Literary Conference in Lisboa—correction, summers without a global pandemic—and what hits me heart-center is a fierce love of Portuguese culture by attendees with little or no Lusitanian blood. (There are many workshops for all genres and disciplines, and a huge mix of people, including Portuguese authors.) In my class, students with Luso or Lusa roots come via Africa, Jamaica, India, Brazil, Canada, the U.S. There is a sense of discovery, mutual reference points, and generosity of spirit among my students that enriches us. But we also notice how exuberantly the other Disquiet participants blend with the city and people of Lisboa too, and the love story that ensues. That can’t be faked. (An aside: Portugal’s popularity does bring complex issues, in that the native residents are within all rights to be unhappy about invasions of people driving up prices and home values even as restaurants echo with English.)

I’m wondering if the future will be heart-based, pushing toward a sense of communion united with cultural details or underpinnings. One of the Disquiet organizers, not Portuguese himself, had one of the most joyous weddings I’ve ever attended there, in Portuguese and English, with friends from America and Lisboa, simply because the literature of the country, and the friendships he forged, make him feel like a cousin. Another friend, also without any Portuguese roots, found in fado music what he was seeking about how to tap into grief for his father, and his gratitude makes him love the whole country as his own invented heritage. That makes me proud, about fado but also because the best part of who we are involves such a welcoming embrace. In a stellar, concrete example of this blend of preserving who we are while expanding it is José Batista in New York, who calls his business the Joey Bats Café. He dreamt up a pastéis de nata bakery with his mother, and he is a great example of “going to the blank area of possibility” to find his future because he also creates pop-up venues—these are literally empty spaces. His business is a hit, and he uses Goldbelly for frozen delivery. In following his spark, he’s found an ingenious way of combining our culture and cuisine with new methods and delivery systems, wide avenues. He posts wonderful photos of his mother and avó beaming. He hosts Brazilian dance nights, inviting exchanges of similarities and differences. Purists may not like that he has chocolate-flavored pastéis, but he is open to experimenting, and I must say, I’m always delighted to serve these at dinners in my home as a way of sharing cultural wonders. (One friend, from Singapore, took the empty box home so she could order some herself.)

There are brilliant, as-yet-undiscovered ways of keeping our essence—think of Azorean writer Vitorino Nemesio’s declaration that the people of the islands are born with “their bones dipped in sea water”—and celebrating who we are with one another but also with the human family. I read recently something about the attendance at Portuguese traditional celebrations or dances being way down; what to do about that? I have fond memories of the Holy Ghost festivals and their capes. Joey Batista opened a door to everyone and says, Welcome, and here are a few traditional things for you to enjoy as you wish. Here’s some of your music, and ours, and maybe just some fun dance music for good measure.

He’s a great ambassador for us and offers a fine example of inclusive solutions.

Simone Weil, a mystic, political activist, philosopher, and author, wrote an essay I’ve always kept in the top drawer of my desk, called “Waiting on God.” She wrote it to help students. It’s about learning to wait in the discomfort of uncertainty rather than force answers. Here’s what she says: “Never…is a genuine effort of the attention wasted. It always has its effect on the spiritual plane and in consequence on the lower one of the intelligence, for all spiritual light lightens the mind.” And she said: “If we concentrate our attention on trying to solve a problem of geometry, and if at the end of an hour we are no nearer to doing so than at the beginning, we have nevertheless been making progress each minute…in another more mysterious dimension…it is really light that is desired…and there must be pleasure and joy in the work. Will power, the kind that…makes us set our teeth, defeats the intelligence. We have to press on and loosen up alternately, just as we breathe in and out. Only in this waiting upon God does one find the soul, and in so doing find the souls of others.” This was instruction she offered to aid work in classrooms, but it is a good way to act in this confounding and crowded world for us all.

I’ll leave you with some advice along these lines from the great Fernando Pessoa—another Portuguese genius getting better known by the world. In a book entitled “Always Astonished,” he has a brief section called “I’m riding in an electric trolley car”:

“That girl’s dress I reduce to its material…the light embroidery that borders the part outlining the neck separates itself from me into the silk thread with which it was embroidered, and the work [to create it]. And immediately there unfolds before me…the factories and the workers…and I see the…machines, the dressmakers…The whole world is unrolled before my eyes…I divine the loves, the soul secrets of all those who work so that this woman…in the electric trolley might wear around her mortal neck the sinuous banality of a swatch of dark green silk on less-dark green material. I’m stupefied. The trolley benches…carry me to distant regions, multiplying into industries, lives, realities, everything. I leave the trolley, exhausted and somnambulant. I have lived an entire life.”

Thank you, Fernando Pessoa. What a happy moment when a student told me he posted a note with the words “Always Astonished” on his desk, as his new anthem.

True education is finally about finding more and more blank spaces, the unknown. Out of that, something we did not expect can arise. Writer Katherine Mansfield once posited that we must prepare a garden patch, and mulch and plant and pull weeds, but suddenly one day can bloom the most glorious flower, and it stuns us…because we didn’t plant it. But we tended the ground into receptivity, and the world sent us a gift.

It’s good to be fierce about what we believe and what is true, but there’s a danger to refusing to push past that toward what we should be humbled by: Let’s not be right, let’s be amazed. Let’s not be all-knowing; let’s be awestruck. Find the blank space and silences and let them speak. As we consider for these coming sessions and days what patrimony and legacy mean, in these times of shutting down and solitude, we can also stay eager for the magic of welcoming the bloom we didn’t plant in the ground we dearly cared for.

Follow the threads attached to others. Stay astonished.

Thanks for listening. Thank you again for this honor. Have a joyful, fruitful conference.

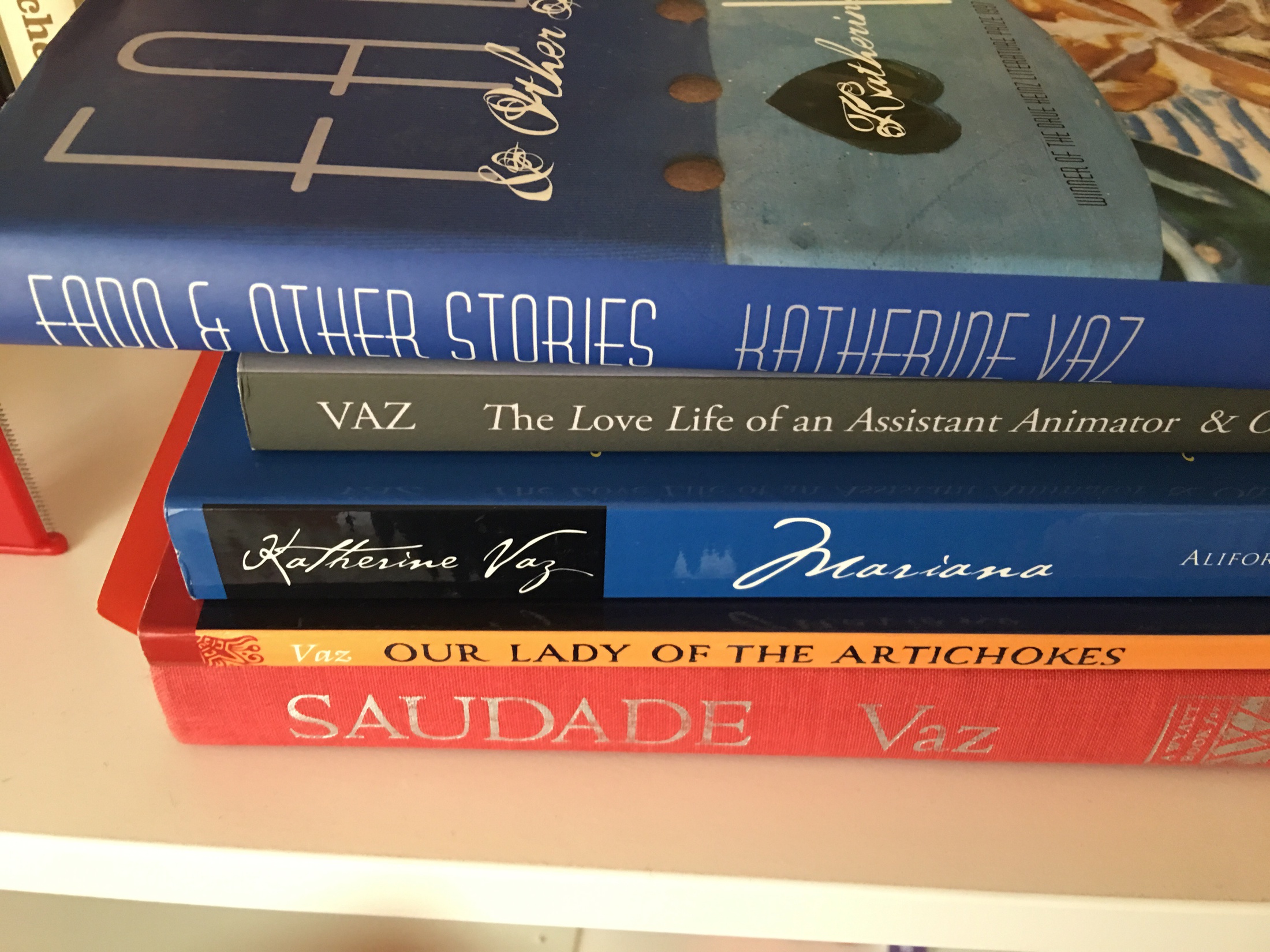

Katherine Vaz has been a Briggs-Copeland Fellow in Fiction at Harvard University and Fellow of the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study. She’s the author of two novels, SAUDADE (a Barnes and Noble Discover Great New Writers selection) and MARIANA, published in six languages and picked by the Library of Congress as one of the Top 30 International Books of 1998.

Her collection FADO & OTHER STORIES won a Drue Heinz Literature Prize and OUR LADY OF THE ARTICHOKES won a Prairie Schooner Award. Her latest book is THE LOVE LIFE OF AN ASSISTANT ANIMATOR & OTHER STORIES (Tailwinds Press, 2017). Her children’s stories have appeared in anthologies by Viking, Penguin, and Simon and Schuster, and her short fiction has appeared in many magazines. She won a New York Film Academy and Writer’s Store national contest for a screenplay idea based on one of her stories.

She’s the first Portuguese-American to have her work recorded by the Library of Congress (Hispanic Division). Other honors include a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship, a citation as a Portuguese-American Woman of the Year, and an appointment to the six-person Presidential Delegation (Clinton) to the World’s Fair/Expo 98 in Lisbon. She lives in New York City with her husband, Christopher Cerf, an Emmy- and Grammy-winning TV producer, composer, editor, and author.